-

Goomtee Tea Estate in DarjeelingDarjeeling is one of the best known “brands” in tea. Even those who don’t drink or care about tea have at least heard the name. But what is “Darjeeling” tea and why is the name so famous?

For starters, Darjeeling is actually a town/district located at the edge of the Himalayan mountain range in northeast India. It’s not Darjeeling tea if it doesn’t come from this district. But the tea plant is not native to this area. The only reason it grows here goes all the way back to the early 1800’s when the British were trying to figure out how to circumvent the Chinese monopoly on tea. The early growing experiments failed, and a native Indian tea plant was later discovered in Assam (Camellia sinensis var. assamica). But these Chinese teas plants brought to the mountains of Darjeeling eventually took root and thrived. The Chinese plants fared better in the higher elevations and cooler temperatures of Darjeeling and stood out for their unique fragrance and complex flavors (most Darjeeling teas are grown between 2,000 and 7,000 feet). Over time the region has developed an international reputation, which has boosted demand and prices.

The reputation is well deserved and came from a number of carefully managed factors. The Darjeeling Tea Association has protected and promoted the Darjeeling “brand” with a French-like zeal (think Champagne), highlighting their unique terroir (the total of environmental factors), beautiful estates, and seasonal variations. Three seasonal variations define the inherent character and flavor of Darjeeling tea.

First Flush

These teas are produced from the first plucking of the new shoots that appear in the spring (March through mid-April) after the plant has come out of its winter dormancy. Like many spring teas around the world, first flush Darjeeling teas are highly sought after and produce a cup that is light, fresh, aromatic, and possess a fair amount of astringency. The dry leaf will often contain a lot of green color, which comes from a long withering process that removes enough moisture to inhibit oxidation, but makes the tea more fragrant.

Second Flush

This is the summer production of teas from the shoots that follow the first flush. In some respects this is more of a “classic” Darjeeling since it tends to bring out those “muscatel” flavors Darjeelings are famous for. The cup tends to be richer, and more full-bodied. It is usually less astringent than the first flush teas and can come off as almost “fruity.”

Autumnal Flush

This last picking of the season doesn’t always get the same attention as the first two flushes, but great teas can still be produced and sometimes purchased at an excellent value. The autumnal flush teas are typically the most full-bodied of the Darjeelings with a more balanced and less astringent cup.Unblended Darjeeling teas should (in our opinion) clearly identify which estate it came from, which flush, and the leaf grade (a series of letter that notes leaf sizes and quality of pluck). We find most of the fine, orthodox teas coming out of Darjeeling will be graded “TGFOP” or “TGFOP1” (Tippy, Golden, Flowery Orange Pekoe – with the “1” denoting exceptional quality). This has always sounded like a bit of “artistic license” to me, but it’s hard to blame them for wanting to present the tea in the best way possible. Ultimately, the leaf and cup will say what needs to be said.

There’s much more that can be said about these wonderful teas from an exotic location. Much of this was a gross simplification, but it’s easy to get long-winded and off track. For the uninitiated, I hope it gives a basic understanding of what these teas are like, where they come from, and how to identify them.Check out our Darjeeling infographic!

Shop Darjeeling Teas

Enjoy!

-Michael Lannier

TeaSource manager -

Black tea is black tea (as opposed to purple tea) because of oxidation. If you cut an apple (or banana or zucchini etc.) in half and let it sit, within a few minutes the exposed flesh start to turn brown. That’s oxidation.

Turning brown: which is perfectly safe, it’s just oxidation

And that is what happens to make black tea. They roll, crush, tear, cut, and/or curl the tea leaves; this is the equivalent of cutting the apple. Thus they expose the interior of the plant, disrupting the cell membranes to air.

A rolling machine in Sri Lanka, crushing the leaves, making them juicy—the precursor to oxidation.

The tea leaves get all juicy, just like an apple gets juicy if you cut it. If they are making black tea, they spread the juicy leaves out on a long flat surface, like a trough, table, or even the floor (using a tarp), and let the leaves turn brown. That's oxidation. If they leave the leaves out long enough, they oxidize fully and become black tea. It is relatively easy to stop or prevent oxidation. Apply gentle heat to the leaves, which kills the enzymes in the leaf and prevents oxidation from occurring, or stops the oxidation at that point. No browning.

Why do tea folks bother with oxidation? Without it, all you would have is white or green teas. I love white and green teas, but if someone took my Grand Keemun away I would go crazy. The date and origin of deliberate oxidation as a process for making black tea is not certain. Fujian has been making what would now be considered black tea since the late Ming dynasty, but large scale production did not take place in China until the 19th century. It is important to understand that for all intent and purposes black tea is NOT drunk in China—at all. They make a remarkable amount and variety of black teas in China, but they don’t drink them. It’s not completely crazy to speculate that oxidation was “invented” by mistake.

What happens during oxidation? The plant gives off H2O (water evaporating) and absorbs extra oxygen from the atmosphere which, with the enzymes in the leaf, triggers a whole bunch of chemical reactions, causing the leaf to turn black/brown, the flavor and aroma to change, etc. etc.

Tea Geek facts about tea oxidation:

- If you really want to be annoyingly literal about it, ALL tea goes through some degree of oxidation, albeit, sometimes a VERY minor degree of oxidation. Because oxidation begins the moment the leaf is plucked from the tea plant.

- -White and green tea both go through probably less than 5% oxidation- basically just what happens during transport and handling-- in fact they are trying to prevent and arrest oxidation. Oolongs can be oxidized through a large range, anywhere from 12- 90%.

- Black teas typically go through close to 95-100% oxidation

- Teas going through oxidation smell AMAZING: intoxicating, addictive, intense, sweet, fruity, alive….

- When black teas are going through oxidation, the leaves are spread out on a surface, maybe a table--that's called the "dhool" table.

- Oxidation is fast, for whole leaf teas it can be up to four hours or so. For a small particled tea (CTC), as little as 90 minutes.

A dhool table (or trough) in Ceylon, the tea would be spread out across these areas.

And yes, there is a purple tea. In fact, there are two kinds of purple tea, both are real tea from the camellia sinensis plant- one from Africa and one from China. Watch this blog for more info.

-Bill

-

To confess, when I was growing up, all "tea" was "black tea" to me. Boring. And as far as I knew, it grew in tea bags that hung from Lipton trees. When green tea had its renaissance in the 90’s as some form of exotic “cure-all”, I began to take interest (and enjoy it thoroughly). But when I learned black and green tea come from the same mysterious source (a plant otherwise known as camellia sinensis), I realized I had been fooled.

The defining feature of black tea, allowing the leaves to fully oxidize, is not as simple as it sounds. There are innumerable factors that go into the process, beginning with geographic location. Local terroir and the particular tea cultivar planted in that region will have a huge impact on the outcome of that tea before the leaves have even been plucked. Local traditions and history may be the biggest factor. China, where black tea originated, has its own unique regional styles. But if the tea growing region was initiated by the former British Empire (India, Sri Lanka, Africa), this will have its own particular impact on the methods used. In Taiwan, their modern black teas are often being produced by the same farmers who have been making oolong tea for decades.

Local traditions and history may be the biggest factor. China, where black tea originated, has its own unique regional styles. But if the tea growing region was initiated by the former British Empire (India, Sri Lanka, Africa), this will have its own particular impact on the methods used. In Taiwan, their modern black teas are often being produced by the same farmers who have been making oolong tea for decades. Even when the regions are inside the same political border, the outcomes can be wildly different. The Darjeeling and Assam regions of India are not geographically far apart, but produce teas that are nothing alike. Part of this is because Darjeeling uses the small-leaf Chinese tea plant, camellia sinensis-sinensis, smuggled out of China by the British spy Robert Fortune. This sub-species prefers high elevations and cooler temperatures. Assam uses their own indigenous plant, camellia sinensis-assamica, whose large leafs produce thick, lush teas and prefer the tropical climate of the Assam valley.

Even when the regions are inside the same political border, the outcomes can be wildly different. The Darjeeling and Assam regions of India are not geographically far apart, but produce teas that are nothing alike. Part of this is because Darjeeling uses the small-leaf Chinese tea plant, camellia sinensis-sinensis, smuggled out of China by the British spy Robert Fortune. This sub-species prefers high elevations and cooler temperatures. Assam uses their own indigenous plant, camellia sinensis-assamica, whose large leafs produce thick, lush teas and prefer the tropical climate of the Assam valley.

My original (and ignorant) assumption was that black tea was somehow boring and homogenous. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The variety is staggering. A well made first flush Darjeeling tea from India and a first grade Keemun from China are so different that it’s hard to recognize both of them as black teas. But that is why it is so fascinating.

-Michael Lannier

TeaSource manager -

Spring is a special time for many cultures. In America we write songs about spring: -Spring Will Be a Little Late This Year -Springtime for Hitler and Germany -Spring Fever -It Might as Well Be Spring In the tea world they make special teas in spring… or do they? [caption id="attachment_216" align="aligncenter" width="604"]The tea bushes from which our 2013 Tai Ping Hou Kui was made. Photo taken April, 2013, Huang Shan Mountain region, Anhui Province, China[/caption] You always hear ‘spring picked teas are the best.’ Like most generalities there is some truth to this, but there are also a lot of exceptions. Why the heck would spring teas be the best anyway? I have spoken to tea botanists about this and their answer makes perfect sense: in most tea growing regions tea plants are dormant during the winter. This means that during those quiet months the plants are recovering from the previous year’s harvest. During that dormant period, and into the very early spring the plants are replenishing those chemicals which in the tea leaves produce those amazing aromas, tactile sensations, and flavors. The leaves will literally have greater amounts of sugars (glucose et al), and various flavor compounds (eg. theaflavins) for that first plucking. If you are a gardener, it is very similar to the fact that the first of the sweet peas or corn or the zucchini or whatever tends to be sweeter, more tender, has increased taste—it’s often bursting with flavor. The same with tea. Spring teas, especially green and white teas can be amazing and truly special. [caption id="attachment_217" align="alignright" width="357"]

Tea fields undergoing drought conditions[/caption] But this only happens if a particular region is having an overall good year for tea. If they are having a drought, too much rain, too cold or too hot the spring teas may not be so great—in fact they can be inferior to the same tea made later in the year. Like always, it comes down to the individual tea. But, make no mistake a great spring tea can make your eyes roll back in your head and your toes curl. [caption id="attachment_218" align="alignleft" width="220"]

Tea fields undergoing drought conditions[/caption] But this only happens if a particular region is having an overall good year for tea. If they are having a drought, too much rain, too cold or too hot the spring teas may not be so great—in fact they can be inferior to the same tea made later in the year. Like always, it comes down to the individual tea. But, make no mistake a great spring tea can make your eyes roll back in your head and your toes curl. [caption id="attachment_218" align="alignleft" width="220"] Fresh plucked, plumb, leaves that will be made into Huang Shan Mao Feng[/caption] When I am considering buying/importing a spring tea from a grower, I always check the spring weather conditions for that region. I very closely examine the dry leaf; I look for tremendous color (specifics can vary depending on the type of tea). I often look for plumpness/thickness in the leaf- I am kind of looking for a Marilyn Monroe type of leaf, not a Kate Moss type. But these are just clues- ultimately everything depends on the steeped cup. Some of the names you will see associated with spring teas are: -88th Night Shincha- a Japanese first flush green tea, plucked on the 88th day of spring -Before the Rain Teas; picking of these Chinese teas begins in late March just before the Qing Ming Festival (around April 5th) and up to around April 20th. -Green Snail Spring: aka Pi Lo Chun, this Chinese green tea may be made throughout the tea season, but traditionally the very best is made in early spring. [caption id="attachment_219" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

Fresh plucked, plumb, leaves that will be made into Huang Shan Mao Feng[/caption] When I am considering buying/importing a spring tea from a grower, I always check the spring weather conditions for that region. I very closely examine the dry leaf; I look for tremendous color (specifics can vary depending on the type of tea). I often look for plumpness/thickness in the leaf- I am kind of looking for a Marilyn Monroe type of leaf, not a Kate Moss type. But these are just clues- ultimately everything depends on the steeped cup. Some of the names you will see associated with spring teas are: -88th Night Shincha- a Japanese first flush green tea, plucked on the 88th day of spring -Before the Rain Teas; picking of these Chinese teas begins in late March just before the Qing Ming Festival (around April 5th) and up to around April 20th. -Green Snail Spring: aka Pi Lo Chun, this Chinese green tea may be made throughout the tea season, but traditionally the very best is made in early spring. [caption id="attachment_219" align="aligncenter" width="604"] TeaSource 88th Night Shincha, 2013[/caption] For most Japanese and Chinese white, green, and oolong teas it is assumed that the spring teas of any particular type of tea will be superior, more aromatic, sweeter, and more flavorful (and more expensive) than a tea from later in the season. And this is often the case. But, you have to taste the tea, you can’t assume a “Spring tea” is going to be better. That is a major part of our job at TeaSource, tasting and evaluating - making sure any “Spring tea” we carry, is worthy of the name. What about black teas? Well, the term often used to describe spring black teas is “first flush” which literally means the first picking of leaves. And this term is most commonly used with Darjeeling teas. Great Darjeeling first flush teas can be amazing. They are usually made in March/April. They can be light, very bright, astringent, somewhat fruity, aromatic, and enlivening. In an interesting marketing twist, black tea growers are starting to use the “flush” terminology to market other black teas, besides Darjeeling. I’ve started to see first and second flush Assams, and even China “first flush” black tea. First flush black teas, while very aromatic and tasty, usually do not have the body or weight of the same tea plucked later in the year. For instance, first flush Assams often are very bright, even crisp, but they tend to be thinner (they don’t have as many bass notes), but second flush Assams are those more traditional Assams with heavy, thick colory, liquors, though they may lack the delicacy and complexity of a spring black tea. It can be a trade-off. But, there are some black teas, particularly from China, that are in their glory as spring harvest teas. For instance, Jin Jun Mei, one of our new spring teas. This black tea is harvested around the Qing Ming Festival and has a truly amazing flavor. [caption id="attachment_220" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

TeaSource 88th Night Shincha, 2013[/caption] For most Japanese and Chinese white, green, and oolong teas it is assumed that the spring teas of any particular type of tea will be superior, more aromatic, sweeter, and more flavorful (and more expensive) than a tea from later in the season. And this is often the case. But, you have to taste the tea, you can’t assume a “Spring tea” is going to be better. That is a major part of our job at TeaSource, tasting and evaluating - making sure any “Spring tea” we carry, is worthy of the name. What about black teas? Well, the term often used to describe spring black teas is “first flush” which literally means the first picking of leaves. And this term is most commonly used with Darjeeling teas. Great Darjeeling first flush teas can be amazing. They are usually made in March/April. They can be light, very bright, astringent, somewhat fruity, aromatic, and enlivening. In an interesting marketing twist, black tea growers are starting to use the “flush” terminology to market other black teas, besides Darjeeling. I’ve started to see first and second flush Assams, and even China “first flush” black tea. First flush black teas, while very aromatic and tasty, usually do not have the body or weight of the same tea plucked later in the year. For instance, first flush Assams often are very bright, even crisp, but they tend to be thinner (they don’t have as many bass notes), but second flush Assams are those more traditional Assams with heavy, thick colory, liquors, though they may lack the delicacy and complexity of a spring black tea. It can be a trade-off. But, there are some black teas, particularly from China, that are in their glory as spring harvest teas. For instance, Jin Jun Mei, one of our new spring teas. This black tea is harvested around the Qing Ming Festival and has a truly amazing flavor. [caption id="attachment_220" align="aligncenter" width="604"] The bushes from which our Jin Jun Mei was made, photo taken March, 2013, Wuyi County, Fujian Province, China[/caption] [caption id="attachment_222" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

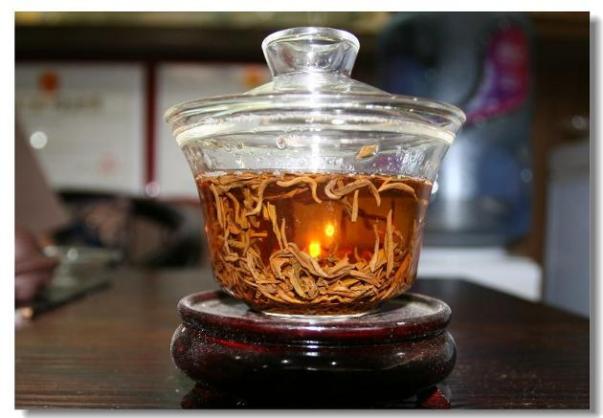

The bushes from which our Jin Jun Mei was made, photo taken March, 2013, Wuyi County, Fujian Province, China[/caption] [caption id="attachment_222" align="aligncenter" width="604"] The golden leaves and golden liquor of Jin Jun Mei in a Chinese traditional gaiwan.[/caption] If spring teas are so great, why is TeaSource featuring them in the fall? Even though it is the 21st century, it still can take 1-4 months to get teas from origin to Minnesota. Some spring teas we air-ship and get them within a few weeks of harvest, and we make them available immediately. Other spring teas, for various reasons, we have to ship by sea and this can easily take 2-4 months. Chinese teas have been particularly challenging the last few years, as the Chinese government has tremendously increased the inspections on any export food item, like tea. This means Chinese teas are some of the safest in the world, but it really increases the amount of time it takes to get them to Minnesota. So, all September, we are featuring most of our 2013 spring teas. Remember we’ve already weeded out the ones that weren’t Marilyn Monroe-ish. All that is left are those spring teas that stop you in your tracks, take your breath away, and leave you struggling to find words. Enjoy.

The golden leaves and golden liquor of Jin Jun Mei in a Chinese traditional gaiwan.[/caption] If spring teas are so great, why is TeaSource featuring them in the fall? Even though it is the 21st century, it still can take 1-4 months to get teas from origin to Minnesota. Some spring teas we air-ship and get them within a few weeks of harvest, and we make them available immediately. Other spring teas, for various reasons, we have to ship by sea and this can easily take 2-4 months. Chinese teas have been particularly challenging the last few years, as the Chinese government has tremendously increased the inspections on any export food item, like tea. This means Chinese teas are some of the safest in the world, but it really increases the amount of time it takes to get them to Minnesota. So, all September, we are featuring most of our 2013 spring teas. Remember we’ve already weeded out the ones that weren’t Marilyn Monroe-ish. All that is left are those spring teas that stop you in your tracks, take your breath away, and leave you struggling to find words. Enjoy.

-

After nearly six weeks of travel, I am back in Minnesota. In addition to the piles of mail on my desk, there are many packages of tea from all over the world, waiting to be evaluated. Last week, we laid out 19 different Darjeeling 2nd flush samples to cup and evaluate.Everyone always thinks this is one of the coolest things about my job, tasting teas, and sometimes it is. Yesterday, however, was not one of those days. Nineteen Darjeeling teas in a row and out of all of them there were only two remote possibilities. And even those two weren’t that great, they were only OK. That’s 90 minutes of my life I wish I had back, and boy did I have cotton-mouth. But that is a major part of my job; tasting mediocre teas, so our customers don’t have to. And it just means I have to work a little harder to find some great 2nd flushes, and I’m confident we will. We’ll keep you informed. -Bill